First DNA Exoneration

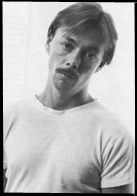

Gary Dotson (Photo: Robert Drea)

Gary Dotson

The rape that wasn't — the nation's first DNA exoneration

The forensic DNA age dawned with little fanfare on August 14, 1989, when the emerging technology exonerated a hapless high school dropout from a working-class suburb of Chicago of a rape that in fact had not occurred.

Gary Dotson had been convicted a decade earlier, when he was 22 years old, based on a story fabricated by his presumed victim, Cathleen Crowell.

On the night of July 9, 1977, a police patrol officer happened upon Crowell, then 16, standing beside a road not far from a shopping mall in Homewood, a suburb of Chicago, where she worked as a fry cook and cashier in a Long John Silver's seafood restaurant. Her clothing was dirt-stained and in disarray.

Crowell tearfully told the officer that, as she walked across the mall parking lot after work, a car with three young men in it darted toward her. Two of the men jumped out, grabbed her, and threw her into the backseat. One of them climbed in beside her and the other joined the driver in the front. The man in the back tore her clothes, raped her, and scratched several letters onto her stomach with a broken beer bottle. "I tried to fight him off," she said, "and I couldn't."

Unintended consequence

Crowell ultimately acknowledged that she had made up the entire scenario and inflicted superficial injuries on herself because she feared that she might have become pregnant through consensual sex with her boyfriend the previous day. Her intent in faking the crime had been only to create a plausible explanation — something to tell her parents — in the event her fear came true, which it would not. It had not occurred to her that there could be official involvement.

The officer took Crowell to South Suburban Hospital, where a rape examination was performed. Her underpants were found to contain what misleadingly would be referred to as a seminal stain — it actually contained a combination of semen and vaginal fluid — extending for 11 inches up the back of the garment from the crotch to the waistband.

The underpants and several hairs, which were recovered from a combing of her pubic area, and a vaginal swab were preserved as evidence. The emergency room physician also made a drawing of the marks on her stomach, indicating that each letter had been formed by a series of superficial scratches appearing in a peculiar crosshatched pattern; the intent could have been to spell love and hate, but the letters were not legible enough to say for sure.

Hoax gets out of hand

Three days later, at the request of police, Crowell's parents took her to the Homewood police station, where she worked with a sketch artist to make a drawing of the invented assailant. She described, and the artist drew, a young white man with stringy shoulder-length hair, but no facial hair.

Two days after that the police showed her a mug book, from which she identified a photograph of Gary Dotson. She said later that the police pressured her to pick the photograph, pointing out how closely it resembled the composite sketch, although police denied the allegation. In any event, Dotson was arrested the next morning at his nearby Country Club Hills home, where he lived with his mother and sister. Although Dotson had a mustache that he could not have grown in five days, Crowell proceeded to "positively" identify him in a police lineup.

At Dotson's trial in the south suburban Markham branch of the Circuit Court in May of 1979, the prosecution presented two substantive witnesses. One was his presumed victim. She was a student at Homewood-Flossmoor High School, where she swam on the junior varsity swim team, studied Russian, and was regarded, generally, as a model of hard work and achievement. She identified him in open court, declaring, "There's no mistaking that face." The second witness was Timothy Dixon, a state police forensic scientist assigned to the case. Dixon began his testimony, setting the tone for much of what was to follow, by falsely claiming to have done "graduate work" at the University of California at Berkeley. In fact, he had only attended a two-day extension course there.

Perjured forensic testimony

Dixon proceeded to testify that he had detected type B blood antigens in the stain in Crowell's underpants. As a result, he asserted, the man from whom the semen emanated had to have been a B secretor — someone with type B blood who secreted his blood antigens into his other bodily fluids. Because Dotson was a B secretor, and because B secretors comprise only 10% of the white male population, this testimony substantially corroborated Crowell's identification of Dotson, whose defense was mistaken identity. The bottom line of Dixon's testimony was that, if Crowell had identified the wrong man, she had done so in defiance of ten-to-one odds.

The trouble was, Dixon was not telling the truth, or at least not the whole truth. It was true that there was B antigenic activity in the stain. It was true that Dotson was a B secretor. But it was not true that the semen had to have come from a B secretor. In truth, Crowell also was a B secretor — a fact there can be no doubt Dixon knew because it was in his laboratory notes. This meant that Crowell's vaginal secretions alone could have accounted for the B antigenic activity in the stain.

Because Crowell was a B secretor, only A and AB secretors could be eliminated as sources of the semen. That is because antigenic activity does not emanate from non-secretors, regardless of blood type, and type O blood contains only H substance, which also is present in all other blood types. Together, A and AB secretors make up only about a third of the population, leaving two-thirds — all persons with types B and O blood and all non-secretors — who could have contributed the semen. Thus, the truth was that the seminal content of the stain could have come from two out of three men in the white population — rather than the one in ten, as Dixon swore under oath.

Prosecutorial misconduct

Turning to the loose hairs recovered from the victim, Dixon testified that "several" were "microscopically similar" to Dotson's. Evidence that came to light later would prove this contention also false. Even assuming it were true, however, the lead prosecutor in the case, Assistant Cook County State's Attorney Raymond Garza, deceivingly exaggerated the point in his closing argument. Garza told the jury that the recovered pubic hairs "matched" Dotson's, although in fact there was then, in the pre-DNA era, no test capable of matching hairs with a source.

That exaggeration was no isolated error. Garza made various other prejudicial assertions regarding the evidence. For instance, he referred to Crowell as "a 16-year-old virgin" although there was no evidence to support such a claim, which, it ultimately became obvious, was not true. He proclaimed that the state "wouldn't have put Mr. Dotson on trial if in any way we knew he hadn't done the crime." And he branded as "liars" the only witnesses called by the defense — four friends of Dotson's who testified that he was with them, drinking beer, watching television, and dropping in at two parties, at the time Crowell claimed to have been raped. Unable to shake the alibi witnesses, Garza told the jury that the testimony simply was too pat to be believed. There invariably are inconsistencies in sound alibi testimony, he explained, and the lack of any in the witnesses' accounts rendered them unworthy of belief.

Although Dotson's lawyer, Assistant Cook County Public Defender Paul T. Foxgrover, failed to challenge Dixon's false testimony, he did object to most of Garza's prejudicial arguments and to the exaggerated contention concerning the hairs. However, the trial judge, Richard L. Samuels, without exception, overruled Foxgrover's objections.

Inconsistencies ignored

Foxgrover also failed to exploit obvious inconsistencies in the prosecution case, several of which were glaring: Crowell had described the rapist as clean-shaven, but Dotson had a healthy mustache when he was arrested just five days after the alleged crime. She claimed that she had scratched the rapist's chest, but Dotson bore no scratches. And neither Dotson nor any of his known acquaintances had a car matching the description Crowell provided.

There was, additionally, an even more telling inconsistency, although to have discovered it, Foxgrover would have needed an independent forensic analysis, which he had neither the funds nor, apparently, the desire to obtain. It was not until 1985, after the victim's recantation, that Edward T. Blake, a Berkeley-educated Ph.D. forensic serologist retained by Dotson's new lawyer, discovered that Crowell had not been raped — at least not at a time consistent with her story.

What Blake discovered was that the concentration of spermatozoa in the stain on Crowell's underpants was two to three times greater than the concentration of spermatozoa on the vaginal swab made at the hospital only a couple of hours, at most, after the presumed rape. Spermatozoa are metabolized in a vagina, reducing their concentration. In a stain on a garment, although the sperm die, the concentration is not reduced. Thus, had Crowell been raped at the time she claimed, the concentrations in the stain and on the swab should have been roughly equal.

Blake's finding, which was confirmed by Henry C. Lee, a well-known Connecticut State Police scientist retained by the state, could only mean that the sexual encounter presumed to have been a rape shortly before the vaginal swabbing in fact had occurred much earlier. Bottom line: Crowell had not been raped, at least not in a manner consistent with the story she was telling. Blake's finding, on the other hand, strongly corroborated her eventual admission that the stain had resulted from a consensual sexual encounter with her boyfriend the day before she claimed to have been raped.

Based on the evidence presented in court, however, the jury found Dotson guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Judge Samuels sentenced him to 25 to 50 years for rape and another 25 to 50 years for aggravated kidnapping, the terms to be served concurrently. On appeal, Dotson's appellate defender was unaware of the problem with the forensic testimony and did not raise the issue. Instead, the appeal focused on Garza's improper conduct and the various known inconsistencies in the evidence. The Illinois Appellate Court ignored the problems, upholding the conviction in 1981. People v. Dotson, 99 Ill. App. 3d 117 (1981).

"Victim" recants

In 1982, Crowell married a Homewood-Flossmoor High School classmate, David Webb. They moved to Jaffrey, New Hampshire, where they joined the Pilgrim Baptist Church. In early 1985, Cathleen Crowell Webb, as she was now known, told her pastor, the Reverend Carl Nannini, that she was riddled with guilt because she had fabricated a rape allegation that had sent an innocent man to prison. She said she had invented the story because she feared that her boyfriend at the time, David Bierne, had made her pregnant, and she thought she needed a cover story if that turned out to be the case. She added that she had inflicted the superficial cuts on her stomach and had torn her clothing to fortify the false claim.

On Webb's behalf, Pastor Nannini contacted John McLario, a lawyer and devout Baptist from Menomonee Falls, Wisconsin, who promptly agreed to represent her. McLario thought it a bizarre but simple case. When he contacted the Cook County State's Attorneys Office, however, he found the prosecutors unresponsive. Because the prosecutors were uninterested in revisiting the case, a friend in Chicago put McLario in touch with Jim Gibbons, an on-air reporter at WLS-TV, the ABC owned and operated station in Chicago.

Gibbons broke the story of the recantation on March 22, 1985. The next morning's Chicago Sun-Times devoted most of its front page to the story, but the Chicago Tribune deemed it worthy of only a small inside story. The Tribune story included a sentence that set the tone for much of the paper's ensuing coverage of the case: "A source close to the investigation called the woman 'unstable'." That was the opening salvo in a guerrilla campaign of not-for-attribution half truths and personal slurs waged by the State's Attorney's Office to discredit Webb and Dotson; although he Tribune has changed significantly for the better in recent years, it was then an accommodating public relations outlet for prosecutors.

Dotson's release on bond

With public sympathy seemingly in Dotson's favor, Judge Samuels on April 4, 1985, ordered his release on $100,000 bond, pending a hearing one week later, on April 11. Samuels acted in response to a petition filed by Warren Lupel, a commercial lawyer who had taken on the case as a favor to a client for whom Dotson's mother worked.

Lupel's petition, which asked that the conviction be set aside, raised eyebrows among members of the criminal defense bar because he filed it under the Illinois Civil Practice Act, which automatically sent the case back to the original trial judge. Just as easily, Lupel could have filed the petition under the Illinois Post Conviction Act, which would have sent the case to a different judge. If Lupel committed a tactical error, however, it appeared beside the point when Samuels set bond at $100,000, permitting Dotson to walk out of prison when a private benefactor posted 10% of that amount in cash.

Samuels appeared to be on the verge of going further on April 4, vacating the conviction and ordering a new trial. Had he done so, practically speaking, it would have been the end of the case. In the face of the recantation of the complaining witness and the problems with the forensic evidence, there is little chance that the prosecution could have tried Dotson again. However, the prosecution asked Samuels to delay his ruling.

J. Scott Arthur, the supervising assistant state's attorney in the Markham branch court who had taken over the case from Raymond Garza, told Samuels that the prosecution had located Webb's former boyfriend, David Bierne, and wished to conduct new forensic tests to be sure that his blood type was consistent with Webb's recantation. Samuels acquiesced, setting the next hearing for April 11, 1985.

Disinformation

The tide began to shift against Dotson on April 10, the day before the scheduled hearing, when the Chicago Tribune published a front-page story stating that new forensic results cast doubt on Webb's claim that the semen in her underpants was David Bierne's. The article, written by reporters Ann Marie Lipinski and John Kass, quoted unidentified sources as saying that "recent blood and saliva samples taken from [Beirne] do not match the evidence police found on [Crowell] in 1977 when she first claimed to have been raped."

The leak on which the story was based relied upon a incorrect assumption. The reporters apparently had fallen victim to the same sleight of hand with which Timothy Dixon had deceived the Dotson jury a decade earlier: If Dixon had been correct that the semen could have come only from a B secretor, it could not have come from Bierne. The new tests ordered by the prosecution, and leaked to the Tribune even before being shared with Dotson's lawyer, determined that Bierne was an O secretor. Thus, contrary to the Tribune report, the test included him among possible sources of the semen in the underpants.

The false story was of little concern to Warren Lupel because the prosecution-ordered new forensic report substantially corroborated Webb's recantation. Although the report, which had been prepared by Mark Stolorow, chief forensic serologist of the Illinois State Police, was written somewhat cryptically, it clearly acknowledged the error of Dixon's claim that the semen could have originated only from a B secretor — such as Dotson. And, the Tribune article notwithstanding, the Stolorow report confirmed that the semen could have come from, among others, O secretors — a group that included David Bierne.

Tactical error

At the April 11 hearing, however, Warren Lupel made an unfortunate tactical error. In an ill-conceived effort to reinforce the already-strong alibi, which was a matter of record from the trial, he called one witness who had not testified previously. The witness was Bill Julian, Dotson's best friend. Julian's testimony contradicted the other witnesses on the question who had been driving the evening of the crime, when the group dropped in at two parties. At the trial, the witnesses unanimously stated that one of the young women had been driving, but Julian now claimed that he had been the driver.

The truth was that Julian had been driving. The trial witnesses later acknowledged outside of court that they had lied about the fact initially out of fear that the truth might get Julian into trouble because he was driving on a suspended license. Lupel was taken by surprise when J. Scott Arthur declared in his closing argument at the April 11 hearing that the inconsistency proved the old adage, "If you give a guilty man enough rope, he'll hang himself."

The prosecution, having branded the alibi as unworthy of belief at the trial because it lacked inconsistency, now branded it so because an inconsistency had emerged. Lupel saw the irony of the situation, but could not respond. He had been blind-sided. He did not learn the truth until after the hearing, when it was too late.

Back to prison

Ignoring the exculpatory new forensic evidence, Judge Samules announced at the conclusion of the hearing that it seemed to him that Webb's trial testimony was more credible than her recantation. He revoked the bond he had approved one week earlier, sending Dotson back to prison. "I failed him," said Lupel.

In the following days, the Tribune increased the tempo of its prejudicial fusillade, including a Sunday front-page piece reinforcing the notion that Webb might be unstable. At last, a source was quoted by name — Assistant State's Attorney Margaret Frossard, who had cross examined Webb at the hearing before Samuels two days earlier. "I was expecting her to be exactly as she had been on television, open and straightforward," said Frossard. "I found that not to be the case. She seemed calculating, evasive, and manipulative."

Despite the pro-prosecution spin of the Tribune coverage, however, significant public sentiment seemed to remain on Dotson's side. Petitions were circulated demanding his release and, for days running, several local and national radio talk shows were devoted almost exclusively to the case. Hoping to capitalize on the favorable sentiment, Lupel on April 19 petitioned Illinois Governor James R. Thompson for clemency.

Propitious timing

The timing could not have been better. The high-profile case was just the thing to distract attention from a controversy over the Thompson administration's handling of a massive salmonella outbreak that had begun on March 29. Although the source of the poisoning was immediately suspected to be a dairy operated by Jewel Food Companies, the Thompson administration had allowed the dairy to continue operating until it voluntarily closed under public pressure on April 9, just two days before Dotson was sent back to prison. By then, the outbreak had become the worst in U.S. history, infecting more than 15,000 residents of Illinois and surrounding states.

Thompson was on vacation during the early days of the crisis, and Illinois Department of Public Health Director Thomas B. Kirkpatrick, a Thompson crony with no background in disease control, left the country on a vacation of his own on April 3, at the height of the outbreak. Thompson did not find out that Kirkpatrick was gone until April 11. Thompson then fired Kirkpatrick "for not having any common sense."

Guilty but popular

No Illinois governor had ever presided over a clemency hearing. Normally, the governor just receives a report from the Illinois Prisoner Review Board. But Thompson announced that the interests of justice demanded his personal attention in this case.

The three-day hearing, from May 10 through May 12 was an international media spectacle. It was held in the main auditorium of Chicago's recently completed State of Illinois Building, soon to be renamed the James R. Thompson Center. The Illinois Supreme Court had reinstated Dotson's bond on April 30, making it possible for him to appear in person. His testimony was carried live on several television stations, as was Webb's. A huge image of her stained undergarment was projected onto an overhead screen at the front of the auditorium. The stain, 11 inches long, was the object of a great deal of attempted humor among the audience, which comprised scores of reporters from Chicago and around the world.

In the end, the Prisoner Review Board voted unanimously to deny clemency and, after taking the matter under advisement for several minutes, Thompson announced to assembled media that Dotson's trial had been fair. In fact, he said, the evidence of his guilt was stronger now than originally. Nonetheless, Thompson said, he had decided to commute Dotson's sentence to time served, in effect proclaiming Dotson popular but guilty and proclaiming the Illinois criminal justice system sound and pure.

What commuting the sentence actually meant was that Dotson would be on parole, which meant, in turn, that any violation of the norms of society could be and, as Dotson soon learned, would be punished without the rigmarole of formal charges or a trial.

Truth shunned

What would be left unsaid by the mainstream news media was that Thompson had stacked the deck: He approved all of witnesses, studiously avoiding any that stood to embarrass the forensic operation of the State Police, and would not permit cross-examination. Edward Blake, for instance, who had reliable scientific results discrediting the original allegation and corroborating the recantation, was not called.

Nor did Thompson permit the testimony of Charles P. McDowell, who had conducted the most comprehensive study of false rape allegations ever undertaken. McDowell, a Ph.D social scientist employed by the US Air Force Office of Special Investigations in Washington, D.C., had developed a 12-point model of the false rape allegation, based on a study of 1,218 reports of rape between 1980 and 1984 at Air Force locations worldwide. Of the reported cases, 460 were proven genuine, 212 false, and 546 were not resolved.

Based on his model, McDowell would have told the Prisoner Review Board that there was no serious doubt that Crowell fabricated her rape allegation. The scratches on her abdomen were the most important indicator that the story was a lie, McDowell said in an interview published in the June 1985 Chicago Lawyer.

The incredible lie

In an article headlined "The Incredible Lie," Chicago Lawyer quoted McDowell: "The physical injuries of false victims are usually superficial — minor cuts, scratches, or abrasions. Although they may appear to be extensive, they don't amount to much. The cuts and scratches virtually never cross the eyes, the lips, the nipples, or the vagina. You typically see a peculiar hatching or crosshatching effect in the scratches.

"What happens here is that the false victim scratches herself but does not immediately see a welt. She thinks she must not have done it hard enough, so she does it again. She applies another scratch, coming from a slightly different direction. By the time the welts begin to appear, you get this hatching. You do not see that in legitimate cases.

"I know of no case in which a legitimate rape victim had words or letters scratched onto her body, but we have encountered it fairly frequently in false accusations. Such scratches often appear on the abdomen, and the scratches are virtually never serious enough to leave scars."

Most of the 11 other points in McDowell's false accusation model also were present in the Dotson case. For instance, false accusers typically claim, as did Crowell, that they offered vigorous and continuing physical resistance, yet suffered no serious reprisals. Most actual rape victims do not strenuously resist and the few who do typically suffer brutal reprisals.

Maladjustment

Gary Dotson did not adjust immediately to freedom. "To suddenly come out with a blast and be slammed into a new environment was really hard," he told journalist Civia Tamarkin, a People magazine special correspondent who was convinced of his innocence. "I had learned to live a different way for six years." He turned to booze. "Drinking relaxed me, made me more open, made me more confident." He said he had a six-pack for breakfast the morning of April 11, the day Judge Samuels sent him back to prison.

As soon as the Illinois Supreme Court reinstated his bond on April 30, Dotson resumed where he had left off. During the clemency hearing, beer was virtually his only sustenance. He had four each morning before the proceedings began, a few more during the lunch break, and at night he drank until he passed out.

After the governor commuted the sentence, Warren Lupel kept up efforts to win a new trial. Dotson, however, lost interest. His primary interest, it seemed, was drinking beer in the company of a 21-year-old bartender, Camille Dardanes, who befriended him during the hearings. At the insistence of friends who assured him he would be "set for life," he signed book and movie contracts. From these, he would realize only a pittance because the projects would not come to fruition.

Cathleen Crowell Webb, however, gave him $17,500, which she received as an advance from a religious publisher to tell her story for a book. With cash in hand, Dotson eloped to Las Vegas with Ms. Dardanes.

The newlyweds bought two used cars, rented and furnished an apartment, and kept current on their daily drinking expenses, at least temporarily. But two months after the wedding, they were broke. Then, in March of 1986, they were evicted from their apartment and moved in with Dotson's widowed mother, Barbara, in Country Club Hills. The new Mrs. Gary Dotson found work as a waitress, but Dotson remained unemployed and, it seemed to him, unemployable. He answered want ads for a while, but no one seemed to have the slightest interest in hiring. "I felt," he said, "like I was carrying a neon sign that said, 'Gary Doston, convicted rapist'."

In January of 1987, Camille Dotson gave birth to a daughter. Although still unemployed, Dotson joined Alcoholics Anonymous, in a short-lived stab at responsibility. Soon, however, on the way home from AA meetings, he started dropping by taverns for a few beers. He was stopped once, while drinking, but escaped with only a speeding ticket, for which he paid a $50 fine.

Sunday in the park

The afternoon of August 2, 1987, a Sunday, the Dotsons took their daughter and a six-pack to Oak Street beach in Chicago. Later they met friends, with whom they continued drinking. On the way home that evening, Gary and Camille got into an argument. Camille, who was driving, stopped the car in the middle of the street. She tried to get out, but Gary stopped her and ended up slapping her. Then he stormed out of the car, with the baby. Camille was chasing them down the street when a squad car happened by. Camille stopped the squad car and told the two officers that her husband was a convicted felon and had taken their baby.

After police found Gary and Ashley down the street, sitting on a curb, Camille told the police that he had struck her and that she wanted to press charges. "I just thought it would shake some sense into him," she told Civia Tamarkin later. "I didn't want him to go to jail. Everything just got out of hand."

On the basis of Camille's complaint, Gary was arrested, charged with domestic battery, and ordered to appear in domestic violence court on August 27. Because the charge, if proved, constituted a parole violation, he was held without bond.

Journalist recruits counsel

Civia Tamarkin, incensed by what she viewed as over-reaction to a relatively minor incident, coupled with the governor's earlier disingenuous action in the case, set out to find Dotson a new lawyer. First, she called Thomas D. Decker, a well-known Chicago criminal defense lawyer she knew from his recent work on a high-profile case known as the "Dream Murder." Decker said he was too busy to take the case, but recommended several other lawyers he thought might take it.

Thomas M. Breen, a former assistant Cook County State's Attorney, was among the lawyers Decker recommended. Based on what he had read about the case, Decker was skeptical that Doston was innocent. "Oh, the schmuck probably did it," was his response when Tamarkin told him the purpose of her call. But Breen said the case fascinated him. At Tamarkin's urging, he agreed to talk to Dotson. Then, after thinking it over for a day or so, he accepted the case.

Initiation of Thomas Breen

On August 27, 1987, Breen successfully argued against a prosecution motion to delay the domestic battery case until September 4. He persuaded Judge William Ward that the motion was just a ploy to keep Dotson in jail a few extra days, until the state faced the fact that there was no case as a result of Camille Dotson's refusal to cooperate. Indeed, immediately after Judge Ward denied the motion, the State's Attorney's Office dropped the charges. Breen assumed that meant his client was free to go. He was wrong.

The Illinois Department of Corrections slapped a "parole hold" on Dotson, requiring that he be held in jail pending a hearing before the Illinois Prisoner Review Board on September 4. By administrative fiat, the Department of Corrections accomplished precisely what the State's Attorney's Office had tried but failed to accomplish in court. But there was no remedy.

At the Prisoner Review Board hearing, Breen first established that Camille Dotson had suffered no bodily harm, contrary to police allegations. Then Breen called Dotson's parole officer, Phillip Magee, to testify. Magee read his report aloud to the board. "Dotson's parole violation seemed directly related to chronic alcoholism," said the report. "His violation neither indicated criminal orientation, nor does he appear to otherwise represent a serious threat to public safety."

After excusing the witnesses and counsel, the board met briefly behind closed doors. When the members emerged, Breen asked if a decision had been reached. "No," he was told. "We will notify you." That, alas, was not true. The board not only had reached a decision, but a had told the media what it was. Breen learned from a reporter that the board had revoked Dotson's parole, reinstating his original sentence. That meant that, for slapping his wife, Dotson faced 16 years, one month, and five days in prison.

The promise of DNA

An article titled "Leaving Holmes in the Dust" in the Newsweek magazine of October 26, 1987, caught Breen's attention. The article, written by Sharon Begley, reported the discovery of a technique capable of linking criminal suspects to crimes through DNA Begley described the technique as "the molecular equivalent of dusting for fingerprints,"

"The principle is simple," she wrote. "Every cell in an individual, including those in blood, semen, and hair roots, has the same DNA, the molecule of heredity. Since each person's DNA is unique (unless he is an identical twin), it can be used for identification with near-perfect accuracy. British geneticist Alec Jeffreys of the University of Leicester, who discovered the technique, estimates that the odds against any two unrelated people sharing the same DNA fingerprints are billions to one."

The article said that the technique had been used to resolve a handful of paternity and immigration cases in Britain and, more dramatically, to link a 27-year-old man, Colin Pitchfork, to the rape-murders of two teenage girls near the English village of Enderby.

Although Breen learned upon inquiry that DNA had never been used to exonerate anyone in a criminal case, its potential for doing so seemed obvious. As a result, Breen filed a motion asking the presiding judge of the Criminal Division of the Cook County Circuit Court, Thomas R. Fitzgerald, to order the testing in the Dotson case.

Christmas cheer

On Christmas eve, 1987, Governor Thompson announced that he was giving Dotson "one last chance" by ordering his release from prison for the parole violation. Two days later, however, Dotson was in trouble again. Again, alcohol was a contributing factor.

On December 26, Doston went with friends to the Zig Zag Lounge in Calumet City, a rough-and-tumble town abutting the Indiana line southeast of Chicago. Dotson, who had been drinking, ordered a sandwich, but objected when it came topped with peppers, which he had not ordered. He refused to pay and, during an ensuing argument, allegedly struck a 67-year-old waitress "with an unknown object." He was arrested and charged with theft, battery, and disorderly conduct.

Judge Martin McDonough set Dotson's bond the next morning at only $1,000. The Illinois Department of Corrections, however, slapped another parole hold on Dotson to prevent his release pending yet another Prisoner Review Board hearing, this one set for February 17, 1988.

On December 29, Camille Dotson filed for divorce, alleging that her jailed husband had a "violent and ungovernable temper." A few days later, the criminal charges were voluntarily dropped by the State's Attorney's Office because prospective witnesses cast doubt on the waitress's version of what had transpired at the Zig Zag, and she apparently had second thoughts about repeating her story under oath.

Pleasant surprise

After a hearing on Breen's motion for DNA on January 7, 1988, Assistant State's Attorney J. Scott Arthur told Judge Fitzgerald he had no objection to DNA testing. "If there's any test out there that's going to help us come to the truth, we want to pursue it," he said. The judge gave his tacit approval to the idea, but said he could not rule on the motion because he no longer had jurisdiction in the case. The decision, therefore, was up to Governor Thompson.

A little later in the day, the governor's office announced not only that Thompson approved the proposal, but that the gubernatorial staff already had contacted Alec Jeffreys, who had agreed to do the testing. Given that Thompson and Arthur had gone to seemingly incredible links to avoid the truth all along, their willingness, even eagerness, to have DNA testing done puzzled Breen and gave him pause.

What could it mean? Had they had an epiphany? Had the light suddenly dawned on them? Or might they actually believe DNA would vindicate their actions in the case? Was it possible that they actually had brainwashed themselves into believing Dotson guilty? Or were they carrying cynicism to a new height? Could it be that they were confident the new science would not yield a result on a decade-old sample, but that they could pretend publicly to have left no stone unturned in their unrelenting search for truth? Breen could only wonder.

"A technical violation"

With the criminal charges gone, the Prisoner Review Board on February 17, found that Dotson had violated his parole by failing to call his parole officer on December 24, the day he was released from prison. Breen told the board that Dotson thought he had a reasonable time to call, and had in fact called on December 26, a few hours before embarking on his Calumet City odyssey. The board nonetheless ordered Dotson back to prison for six months.

Terry Barnich, the governor's legal counsel, acknowledged that Dotson's failure to call his parole officer was only "a technical violation" and "wasn't enough to revoke the clemency order" the governor had issued on December 24. Had the board found a "material violation," Barnich opined, Dotson no doubt would have been returned to prison for longer than six months.

Jeffreys test fails

It appeared that Dotson's only hope for avoiding another six months behind bars rested with Alec Jeffreys at the University of Leicester, but there was no cause for optimism. Jeffreys's patented process, known as RFLP, for restriction fragment length polymorphism, required DNA of high molecular weight, meaning that it would not work if the genetic material had lost mass due to degradation.

It was not surprising, therefore, when Thompson announced on April 7, 1988, that Jeffreys had been unable to obtain a result. "The evidence was simply too stale," said the governor. "We gave it our best shot, as far as it's humanly possible to go in search of the truth . . . far beyond."

New testing

Thompson soon learned, however, that it was humanly possible to go one step further: There was another type of DNA testing, known as PCR, for polymerase chain reaction. The PCR technique, which had been patented by the Cetus Corporation of California in the mid-1980s, had the advantage of working on degraded samples.

Unlike RFLP, which had the potential to link a specific suspect to a semen sample, to the absolute exclusion of all other men in the world, PRC could only include or exclude a suspect among a group of the population who could have been the source of genetic material recovered from a crime scene.

Although improvements in PCR eventually would make it as discriminating as RFLP had been initially, in 1988 it was capable only of categorizing DNA into 21 different types. The probability of a random match between a suspect and a semen sample ranged from one in seven for the largest category to one in 100,000 for the smallest.

Forensic applications of PCR were being pioneered by Edward Blake, the California forensic scientist whose conventional testing of the evidence in the Dotson case three years earlier had strongly corroborated Webb's recantation. Blake, whose results Thompson had refused to consider in 1985, had been licensed exclusively by Cetus Corporation to use its patented technique. Nonetheless, Thompson ordered that the infamous semen-stained underpants, along with fresh blood samples from Gary Dotson and David Bierne, be dispatched to Blake at Forensic Science Associates.

Absolute innocence

On August 15, 1988, Blake notified the governor, the prosecutors, and Thomas Breen that the PCR testing had positively excluded Dotson and positively included Bierne as the source of the semen in the underpants. The next day, Breen formally asked Thompson to grant unconditional clemency based on actual innocence.

Breen pointed out that the matter should be treated expeditiously, as an emergency, because Dotson was suffering the irreparable injury of ongoing confinement for a crime that had not occurred; although Dotson had been released from prison that very day, having served six months for his technical parole violation, he was involuntarily committed to a residential treatment center for alcohol and substance abuse.

The urgency argument fell on deaf ears. A spokesperson for the governor told reporters that Thompson wanted to be assured of the accuracy of the PCR test and would not act on the clemency question until receiving a recommendation from the Prisoner Review Board.

Back to court

Nine months later, when the Prisoner Review Board still had failed to act, Alec Jeffreys wrote a letter to Breen critical of the Thompson administration's inaction. "In view of the conclusive nature of this evidence, I earnestly hope that you will be able to go back to court on this matter and obtain the release of your client," said the letter, which was dated April 20, 1989. "It is clear that rejection of this evidence by the judiciary would constitute a gross miscarriage of justice."

Breen released the letter to the media on May 3, after filing a new petition for post-conviction relief based on the PCR results. A hearing on the petition was set for August 14 before Judge Thomas R. Fitzgerald, the recently named presiding judge of the Criminal Division of the Cook County Circuit Court.

Prosecutors publicly vowed to oppose the petition, which sought a new trial. By August 14, however, there apparently there had been a change of heart. The State's Attorney's Office joined in the motion. In granting the motion, Judge Fitzgerald said, "It's my belief that had this evidence been available at the original trial, the outcome would have been different."

No sooner had Fitzgerald ruled than the State's Attorney's Office announced that the charges against Dotson would be dropped, thus ending his 12-year ordeal.

"It's been 12 long, long grueling years and I'm relieved it's over," Dotson told reporters outside the courtroom. "The stigma remains. It's something I have to deal with. I've been referred to as a 'convicted rapist.' Now, at least, I'm no longer 'convicted'."

A remaining mystery

After Dotson's exoneration, an elusive aspect of the case continued to trouble observers: How could a 16-year-old girl possibly fabricate a false rape allegation with sufficient credibility to fool a judge, jury, prosecutors, a governor, assorted journalists, and significant segments of the legal community and general public?

The answer, as she later told a psychologist, was that she did not exactly make it up — but rather lifted it from a novel she had been reading. The novel, Sweet Savage Love (Avon Books, 1974), included a vivid rape scene, which included these parallels to Cathleen Crowell's testimony at Dotson's 1979 trial:

She testified that she was abducted by three men in a car and raped by one of them while the others were consistently laughing "like it was a big joke." The woman in the novel was abducted by three men in a carriage and two of them "laughed along with" the rapist.

She testified that she was raped by a man who held her down, "putting his weight on" her as he tore off her clothes. The woman in the novel was stripped by a rapist and "pinned down by his weight."

She testified that after the crime the rapist pushed her out of the car nearly naked. In the book, the men "threw [the victim] onto the ground beside [the carriage] naked."

She testified that she tore the rapist's shirt during the attack. The victim in the novel felt her attacker's shirt "tear under her clutching fingers."

She testified that the rapist bit her breast. The victim in the novel was "pinned down" as the man bit her breast.

—Rob Warden