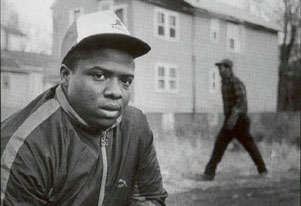

Lavelle Burt

Lavelle Burt (Photo: Loren Santow)

Lavelle Burt, 20, falsely confessed to firing a bullet that killed a child in Chicago's Bridgeport neighborhood on September 19, 1985.

Two days after he confessed, Burt told his lawyer that he was not involved in the murder but had believed the police when they told him he would get probation if he confessed. He said he decided that confessing to a crime he did not commit was better than risking a prison sentence or even the death penalty.

When Cook County Circuit Court Associate Judge Ronald A. Himel was faced with the choice of believing the confession or the recantation, he chose the confession. After a bench trial in October 1986, Himel found Burt guilty of murder based solely on the confession.

While Burt was awaiting sentencing, however, Himel received new evidence that indicated that the child's mother fired the fatal bullet and that Burt had nothing to do with it. Himel reopened the case and acquitted Burt.

The victim of the crime with which Burt was charged, convicted, and acquitted was 2-year-old Charles Gregory, was shot once in the head with a .22 caliber weapon outside his home near Comiskey Park. After the shooting, police discovered gunpowder residue on the child's mother, Carolyn Collins, indicating that she fired a gun. Collins gave conflicting accounts of what happened in different interviews with police and in telling the story to the child's paternal grandmother.

Despite the powder residue and her inconsistent statements, the police chose to focus not on Collins but rather on one of the various stories she told about what happened — that she had seen Burt, a school acquaintance from many years earlier, come across a vacant lot adjacent to her home and fire at two girls, missing them and accidentally hitting the toddler.

Collins told this story belatedly. In her initial accounts, she claimed she did not see what happened. In one version, she said she at first thought the child had been bitten by a dog. In another, she said she heard a shot but saw no one who might have fired it. Only after Collins learned that tests showed that there was gunpowder residue on her — making her the prime suspect — did she implicate Burt.

Collins identified the two girls at whom Burt supposedly fired as sisters, Linda (Fay) Leatherberry and Gloria Leatherberry Walls. Both initially denied having been shot at, but after interrogation Linda stated that she had in fact been shot at by Burt. However, she soon recanted this statement, claiming that the police coerced her to make it by refusing to let her go home until she told them what they wanted to hear.

After taking Linda Leatherberry's statement, police developed a complex theory of Burt's motive for shooting at the girls. Their brother, Robert Leatherberry, had been shot in the leg a day or two earlier by an acquaintance of Burt's. The police suspected that the shooting was gang related and, therefore, that Burt might have shot at the sisters to discourage any thought their brother may have had of testifying against the shooter.

This theory seems to have had little basis in fact. The Leatherberry shooting apparently was accidental. Burt was one of several youths questioned, and after questioning he located the weapon involved and took it to the police. There is no evidence that he was a gang member.

Apparently because they knew Burt from the Leatherberry incident — he had never been in trouble for anything else except under age drinking — the police decided to see if he knew anything about the Gregory shooting. Detective Donald Barton went to Burt's home about noon the day of the shooting. Burt was not home, but his grandmother took Barton's card and promised to have Burt call when he came home. Burt evidently was not a suspect at that time. He called twice before police came to talk to him. When they finally did come and took him to the Brighton Park district station, he was not handcuffed. As he was led into the station Burt said he saw Carolyn Collins. She had not, she would testify later, identified Burt prior to seeing him at the police station.

After hours of interrogation, Burt said Barton and other detectives told him that both Carolyn Collins and Linda Leatherberry had told them he fired the shot that killed Charles Gregory. Because the detective repeatedly suggested that he would be better off confessing that facing the consequences that might flow from not confessing, he said, he decided to confess.

Burt said that during interrogation the officers gave him the details that he reiterated in his confession, which he gave to Assistant State's Attorney Peter J. Troy and a court reporter the next day. After Burt was charged with the child's murder, his first cousin, Thomas Brewer, an assistant Massachusetts attorney general, arranged for him to be represented by Chicago criminal defense lawyer Francis X. Speh Jr. Brewer and Speh worked together several years earlier as assistant Cook County state's attorneys.

When Speh first interviewed Burt in the county jail, Burt recanted and explained why he had confessed in the first place. Because of the gunpowder residue on Collins, the lack of any on Burt, the failure to find the gun, and the conflicted statements made by Collins, Speh came to believe Burt.

Speh said he did not move to suppress the confession because there appeared to be no basis for such a motion. While Burt had asked permission to call home, he had not asked for an attorney, and he had been advised of his right to counsel before he made his formal statement.

The day after Judge Himel found Burt guilty, the deceased child's maternal grandmother, Josephine Collins, arranged for a friend to contact Himel. The friend told Himel that Josephine, who lived with Carolyn Collins and who had attended the Burt trial, had important information about the case. Himel agreed to speak with her, and she told him that, after learning during the trial of the gunpowder residue on her daughter, she checked a .22 caliber pistol in the family home and found a bullet missing. Himel sent police to pick up the pistol, and a ballistics examination indicated it in all probability was the weapon that killed the child.

Himel reopened the case. Despite all the facts favorable to Burt and unfavorable to Collins, the lead prosecutor in the case, John T. Groark, continued to profess that Burt did it. "There was no reason for him to give the statement unless he was there and he did do it." Groark told reporters.

After a brief hearing, Himel concluded otherwise and he acquitted Burt, who later in a Chicago Lawyer interview explained why he had confessed: "They say, 'You're a smart ass. You ain't gonna tell us what happened., I kept tellin' them, 'I dunno what happened.'They slap me around, in the face, a lot of body shots, but that is not what made me give the confession. I gave it because I got scared. I thought I was gonna get convicted of something I didn't do.

"The detective was sayin', 'You're stupid. Nobody believe you meant to do it. You know, everybody know you're not a baby killer. You got a good background and you'll get off with involuntary manslaughter and probation.'

"They told me the two young ladies say they saw me do it. That's when I got scared and started to make the phony confession. They took me to the scene and made me look for the gun an' everything. They asked me, 'Where do you think you might have thrown it?' I picked out an area where someone was growing a garden and I told them, 'I threw it over there.'

"I kept asking if I could call home, but they kept sayin', 'You tell us what happened, and then you can make a call.' I didn't ask for a lawyer. They didn't mention nuthin' about rights until I was going to make a statement. At the time they called in the court reporter was the first time they said anything about rights."

— Rob Warden